Yokoyama Katsuya

横山 勝也

12/2/1934 - 4/21/2010

尺八

|

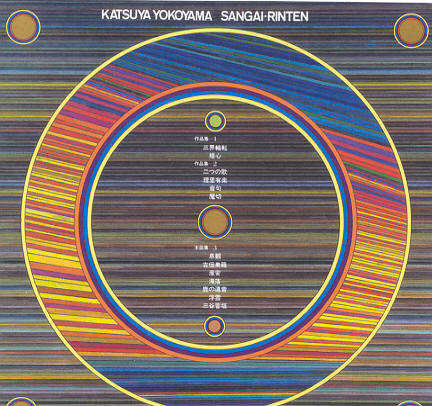

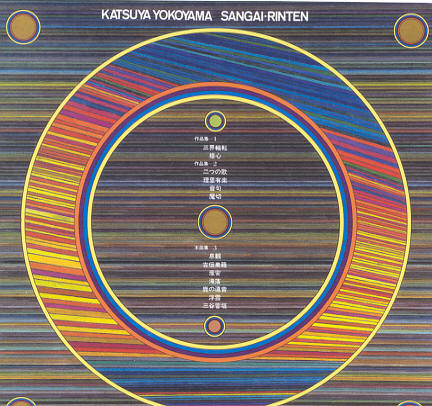

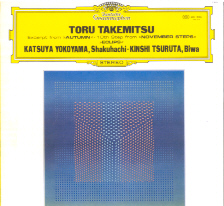

THE WORLD OF KATSUYA YOKOYAMA – By Tomiko KOJIMA, 1980 About four years ago, I suddenly came to a new realization when listening to a recording of Katsuya Yokoyama's performance of "Tsukikusa no Yume ('Dreams of Moonflowers'), a Collection of the Works of Rando FUKUDA. The realization was that of the sweetness of Yokoyama's shakuhachi playing. Up until that time, I had always been surprised to hear the great breadth of expression in his shakuhachi, his ability to give similar passages a completely different character in accordance with the circumstances. And I always wanted to find out what it was that gave him this breadth of expression so different from the shakuhachi playing of other performers. Here I must make a confession. At one of his recitals, Yokoyama performed a number of rather sugary compositions in the new-Japanese music style and I had to ask myself why anyone like Katsuya Yokoyama would perform such pieces with such enjoyment. I decided it certainly must be a bad influence from his teacher, Rando Fukuda. And for that reason as well, I had no intention of listening to his recording of "Tsukikusa no Yume" but happened to do so only because I received the record. Certainly, that recording as well was quite sweet, but I realized unexpectedly by listening to it how much it expanded my perspective of Yokoyama's shakuhachi playing. I have always felt that the sound of the futozao shamisen which accompanies gidayu has an extremely deep sweetness which accounts for its very keen and penetrating as well as very passionate power of expression. As the great futozao masters pass away however, it is now becoming increasingly more difficult to hear that futozao sound which reaches the depths of sweetness. And while I frequently yearn for that kind of sound, I realized that the exact same thing can be said about the sound of the shakuhachi. Yokoyama is also a student of Wadatsumido who almost seems to be at the opposite extreme of Rando Fukuda. I have come to think of the music of Wadatsumido, which emphasizes the spiritual aspect so strongly that, to be frank, I at times wonder if it is not just playing up to the audience, as a modern descendant of Fuke shakuhachi. Yokoyama has been greatly influenced by Wadatsumido and even now he still takes his monthly fee and goes to study with Wadatsumido. It is this spiritually vigorous, sharp and passionate side which overcomes us and draws us in, whether it be in playing a piece of Toru TAKEMITSU's where the sparks fly in exchange with Kinshi TSURUTA’s biwa playing, or making love with a honkyoku piece on stage alone. And it is this side which everyone has come to emphasize as representing Yokoyama's playing style. However, if Yokoyama's shakuhachi had only that side to it, his variety and breadth of expression could not exist. Rather, it is for the very reason that his experience extends to the very sweet and delicate world of Rando Fukuda that his power of expression overflowing with a strong tension of spirituality can come into existence. I recently talked with Yokoyama about how he got started in shakuhachi. Yokoyama's grandfather, Koson Yokoyama, was a shakuhachi performer of the Kawase line of the Kinko school. He was also quite renowned as a shakuhachi maker. Yokoyama himself remembers his grandfather as a great fisherman but has no recollection of hearing him play shakuhachi. As a fisherman, his grandfather designed and made all his own fishing equipment and was apparently quite an eccentric in true Meiji Period fashion. He certainly seems to have had a disposition which somehow would be related to Yokoyama. Yokoyama's father, Ranpo Yokoyama, studied shakuhachi both from his father Koson in the Kinko school as well as becoming a very close student of Rando Fukuda. As for his study of Kinko school, much of it was apparently done by standing outside his home listening to someone else play and stealing their techniques. Yokoyama himself says that "it is only natural to do so. I also learn a lot by listening to other performers." Yokoyama in turn learned Kinko school and the Azuma school shakuhachi of Rando Fukuda from his father. Although the actual number of lessons was very few, Yokoyama did take several directly from Rando Fukuda when the latter was at a very advanced age. Yokoyama says that he actually began shakuhachi with the study of the Azuma school which was fortunate for him. The reason for that is that the Azuma school has completely free fingerings in which the performer uses any fingerings which produce the note desired. It is a very free way of thinking in regards to performance. Yokoyama says that "the fingerings of the Kinko school, for example, are no doubt the fingering habits of some individual of long ago which have since become fixed. For certain traditional pieces such fingerings are no doubt the most convenient, but for performing newer pieces, the free way of thinking of the Azuma school has been very useful." At the age of 24, Yokoyama was deeply moved by a performance of Wadatsumido and went to study with him. He still goes for lessons today. Yokoyama in a sense has a very naive personality, quickly enraptured or deeply moved to tears by someone or something. And it is within this naivety which flows the furious search for shakuhachi music which has spanned three generations, and the ability to perform at such a large and dynamic scale. In the shakuhachi music of Katsuya Yokoyama, the Azuma school, Kinko school and Wadatsumido all come to a splendid unification. The three-record set, Sangai Rinten, certainly commemorates the fruition of Katsuya Yokoyama's music at this point in time. The first two records in particular give a very refreshing look into Katsuya Yokoyama the composer. To be honest, having heard a recording of "Onku" several years ago, I felt that Yokoyama the performer was rather different from Yokoyama the composer. However, in this present recording, both the newly composed pieces and the older ones have a new freshness to them which indicate that Yokoyama the composer has certainly matured both spiritually and technically. In recent years, the composing activities of such traditional music performers as Hozan YAMAMOTO, Susumu MIYASHITA, and Tadao SAWAI have become quite extensive suggesting an end to the leadership of the composing of modern pieces by composers trained in Western music and the beginning of leadership by those composers trained in traditional music. Yokoyama very modestly has said that he has tried composing no matter how bad the result, and when he then plays someone else's composition, he is able to understand and learn a lot about composing. For this record set, in any case, the compositions are all very excellent. And with the better known honkyoku pieces and their superb presentation, it certainly is not an overstatement to say that this set represents Japanese music at its best. Profile Born in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan in 1934, he studied shakuhachi of the Kinko school from his grandfather, Koson YOKOYAMA, and his father, Ranpo YOKOYAMA. In 1959, he studied with Rando FUKUDA and Wadatsumido I. In 1961, he formed the Tokyo Shakuhachi Trio with Kohachiro MIYATA and Minoru MURAOKA, and in 1963, the three of them together helped form the Nihon Ongaku Shudan (Ensemble Nipponia) with the intent of creating a new Japanese music using traditional instruments. Then in 1964, he founded the Shakuhachi Sanbon Kai with Reibo AOKI and Hozan YAMAMOTO which cut across school differences in the shakuhachi world. In November 1967, he performed in New York City in the premiere of Toru TAKEMITSU's "November Steps" with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Seiji OZAWA. Since, he has performed on over eighty different occasions with orchestras in Europe and the United States. He won one of the top awards in the 1973 Japanese Art Festival. He has also performed with the NHK Symphony Orchestra on various occasions including at the opening of the Sydney Opera House and at the 1974 United Nations Peace Concert. He has performed at the Tanglewood Music Festival and the Paris Festival, and today continues his performances and composing both in Japan and abroad. (English adaptation and translation by Richard Emmert)

|

|

先生 教え子

Helen Dryz

Dr James Franklin 1959 - |

アルバム

録音した曲

作曲・編曲

| 尺八 の作品 | |||

| タイトル | 漢字 | 年 | 別題 |

| Shichikuryoin | 糸竹呂韻 |

||

| Onku | 音句 |

1964 |

|

| Sangai Rinten I | 三界輪転Ⅰ |

1972 |

|

| Konton | 渾沌 |

1974 |

|

| Futatsu no Uta | 二つの歌 |

1975 |

|

| Makiri | 魔切(または魔斬) |

1975 |

|

| Sekishun | 惜春 |

1975, 1981 |

Lamenting the Passing of Spring |

| Gaifu | 凱風 |

1976 |

|

| Ririura | 理里有楽 |

1978 |

|

| Ririura Part II | 理里有楽 Part II |

1978 |

|

| Sesshin | 接心 |

1978 |

|

| Sesshin Part II | 接心 Part II |

1979 |

|

| Sangai Rinten | 三界輪転 |

1980 |

|

| Sesshin Part III | 接心 Part III |

1980 |

|

| Kai | 界 |

1982, 1984 |

|

| Shunsui | 春吹 |

1983 |

|

| Hyojo no Uta | 平調の唄 |

1984 |

|

| Kokurai | 虚空籟 |

1984 |

|

| The Shakuhachi Music | ザ・尺八・ミュージック |

1985 |

|

| Gōru | 響流 |

1986 |

|

| 箏 | |||

| Sekishun | 惜春 |

Lamenting the Passing of Spring |

文献

| タイトル | 漢字 | 出版社 | 年 | ページ | 言語 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daiyonkai Yokoyama Katsuya shakuhachi risaitaru [Yokoyama Katsuya's Fourth Shakuhachi Recital] |

Tokyo: Yokoyama Katsuya | 1972 | |||

| Shakuhachi gaku no miryoku [Fascination with Shakuhachi Music] |

Tokyo: Kodansha | 1984 |